Guitar

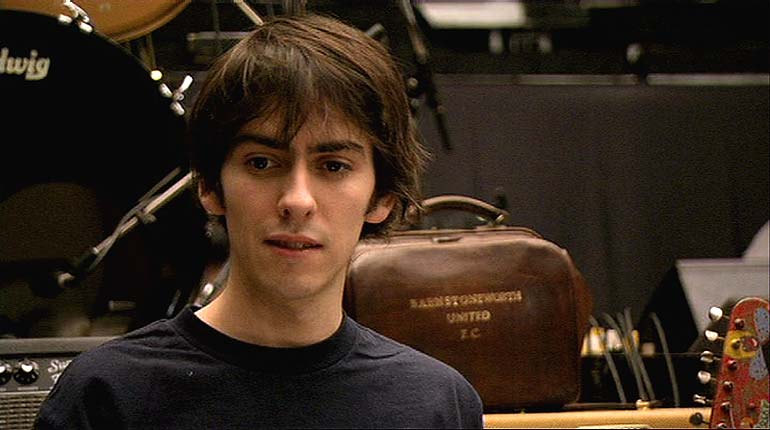

World Interview with Dhani Harrison

January 2003 issue

by Christopher Scapelliti.

In

the final years of his life, George Harrison often predicted that he wouldn't

finish the tracks that make up Brainwashed, his new, posthumously released album

on Dark Horse Records. It wasn't his fight with cancer that the former Beatle

guitarist believed would prevent him from completing the recordings-it was his

own indifference. Harrison had little desire to see his work released in a pop

culture climate controlled by an increasingly cynical and money-grabbing music

industry. An inveterate nonconformist-the mark of a bona fide rock and

roller-Harrison had throughout the 80s become increasingly disenchanted with the

fickle and unsupportive nature of the record business. He spent much of his last

decade at his Friar Park, estate in England, or at his homes in Switzerland,

Australia and Hawaii, preferring the flowers in his gardens to the songs

germinating in his head.

In

the final years of his life, George Harrison often predicted that he wouldn't

finish the tracks that make up Brainwashed, his new, posthumously released album

on Dark Horse Records. It wasn't his fight with cancer that the former Beatle

guitarist believed would prevent him from completing the recordings-it was his

own indifference. Harrison had little desire to see his work released in a pop

culture climate controlled by an increasingly cynical and money-grabbing music

industry. An inveterate nonconformist-the mark of a bona fide rock and

roller-Harrison had throughout the 80s become increasingly disenchanted with the

fickle and unsupportive nature of the record business. He spent much of his last

decade at his Friar Park, estate in England, or at his homes in Switzerland,

Australia and Hawaii, preferring the flowers in his gardens to the songs

germinating in his head.

"He'd always

say, 'One of these days you'll have to finish all this stuff,'" recalls his

son, Dhani, who worked with his father on the new album. "And I'd say, 'Oh,

c'mon, not if you finish them first!' I thought he was joking. But now I

see he was being serious. He was doing the songs for himself, and he felt no

pressing urgency to see them on store shelves." Which is putting it

rather lightly. Brainwashed is, after all, an album nearly 15 years in the

making: its opening track, the tropical "Any Road," dates back to the

heady, healthy days of Cloud Nine, Harrison's 1987 release and, prior to

Brainwashed, his most recent album of new material. In truth, Harrison had

spoken enthusiastically in 1999 of releasing his new songs under the tongue-in-cheek

title, Portrait of a Leg End. But his disinterest, combined with ongoing

health problems-throat cancer in 1997, and a knife attack by an intruder at his

London home in late 1999-ensured that Harrison's record projects were curtailed

in the final decade of his life. With Brainwashed, however, many of his

last songs have finally been released, roughly one year after Harrison's death

from brain cancer on November 29, 2001. As he'd anticipated, it was laft to the

son to finish what the father had begun. Working with producer Jeff Lynne (the

founder of the Electric Light Orchestra and George Harrison's longtime friend

and producer). Dhani Harrison-24 years old and himself an accomplished guitarist

and musician-spent much of the last year putting the finishing touches to 12

demo recordings he and his father had begun in the years before the elder

Harrison's death. "They were what Jeff and I refer to as 'posh

demos,'" says Dhani, explaining the rather upscale quality of his father's

original recordings. "What Jeff and I added were our own guitars, bass,

backing vocals-all the things we would have done anyway had my dad been there.

Basically, I was taking the role of the artist, because I was there the whole

time with my dad. We were very careful to tread lightly-I only ever dared do

anything with this album that I knew my dad would like."

Dhani and Lynne's

respect for the original effort is apparent in the final product: Brainwashed

doesn't only sound complete; its finely focused arrangements and production

suggest the vision of one artist, not three. Although both Dhani and Lynne

are quick to call their work on the album "a labour of love," it is

also evidently the result of tempering their artistic desires to one sympathetic

with Harrison's. Their care is more rewarding for the fact that George

Harrison's songs on Brainwashed are first-rate. Music journalists are

pathologically predisposed to enthuse over the latest works of their graying-or,

in the instance, deceased-heroes. Brainwashed is the all-too-rare instance in

which the results deserve the acclaim. If the quality of the music resembles

anything in Harrison's catalogue, it is his monolithic 1970 solo debut, All

Things Must Pass. Like that album, Brainwashed is full of beautifully melodic

and memorable music and lyrics-songs whose passages can be easily recalled after

just one listen. And, like All Things Must Pass, Harrison's new album is

nakedly spiritual. He was, after all, a follower of the Hindu faith for

much of his life, and as such believed in renunciation of the world, and rebirth

through many lifetimes by reincarnation. Although the songs on Brainwashed are

rarely as broodingly introspective as some on the earlier album-"Beware of

Darkness," "The Art of Dying" and "All Things Must

Pass" come to mind-Harrison stitches together their often droll tales with

his characteristically pragmatic spiritual outlook. On "Any Road," he

sings about the perils of running through life aimlessly, warning, "If you

don't know where you're going/Any road will take you there." The point of

view becomes more personal on "Pisces Fish," as Harrison describes a

landscape full of unexpected obstacles that hinder his progress, with the result

that "ones half's going where the other half's been." Elsewhere on the

album, the ailments that intruded  upon Harrison's sanctuary hang ominously, and

it's here that the lyrics become more confessional. "I never knew that life

was loaded," he sings on "Looking for My Life." "I never

knew that things exploded/I only found it out when I was down upon my

knees/Looking for my life." "Obviously, his illness had an input

into the songs," says Dhani. "And it influenced the way he wrote songs

and the way he saw life. But my dad never let anything get him down. He was a

tough guy. He just got up and carried on."

upon Harrison's sanctuary hang ominously, and

it's here that the lyrics become more confessional. "I never knew that life

was loaded," he sings on "Looking for My Life." "I never

knew that things exploded/I only found it out when I was down upon my

knees/Looking for my life." "Obviously, his illness had an input

into the songs," says Dhani. "And it influenced the way he wrote songs

and the way he saw life. But my dad never let anything get him down. He was a

tough guy. He just got up and carried on."

That attitude, too, is apparent in the record. Far from a study in

self-pity, Brainwashed is a celebration of an individual's ability-Harrison

would likely say "responsibility"-to determine his fate, even when

facing seemingly impossible odds, as Harrison did in his final days.

Nowhere on the album is that spirit stronger than on his final song, the title

track, which is both Harrison's most scathing and most instructive composition.

Against a wall of chiming guitars and other string instruments, he counts the

many ways in which the human race is drummed into submission, beginning with

school, the place in which a teenage, free-thinking Harrison developed his

rebellious streak. He continues on, denouncing kings and queens, Dow Jones

and NASDAQ, the military, the media, computers and cell phones, before

concluding with the plea, "God, God, God, wish that you'd brainwash us

too." "I just love 'Brainwashed' so much, because it's the

realest of all the songs," says Dhani. "It's true-everyone is being

brainwashed by these messages, by taking so much of what we're told and how we

live for granted." For all of his pronouncements on the album,

Harrison makes some of his finest and most beautiful statements courtesy of his

guitar. There is a decided emphasis on his distinctively fluid slide guitar,

particularly on "Never Get Over You" and the instrumental "Marwa

Blues." But the stringed instrument perhaps most prevalent on Brainwashed

is the ukulele, the tiny nylon-stringed instrument long associated with

Britian's mid-20th century music halls and traditional Hawaiian song. "He

loved the uke," Dhani explained. "It just has a great little sound.

And he always loved the tropics. He was a pretty troppo guy."

Not surprisingly, the ukulele was the instrument on which Harrison debuted many

of the album's songs for Jeff Lynne. "George would come by and play them

for me," Lynne recalls, "usually on the ukuele. And I would just go,

'Wow, that's fantastic!' And he'd say 'Well, I'm gonna lay them down roughly, as

demos.' And then, of course, he gave me the honour of finishing them for him. We

would have done it together. Instead, it was left to me and Dhani to

finish." It was not the first time Lynne had been asked to produce an

artist after death. In 1995, at the request of Harrison, Paul McCartney and

Ringo Starr, Lynne produced two new singles for the Beatles, working from a pair

of vocal-and-instrument demos recorded in the Seventies by John Lennon.

Released as part of the group's mid-Nineties Anthology series, "Free As A

Bird" and "Real Love" combined Lennon's voice-and-instrument

cassette recordings with fresh overdubs from his surviving band mates. The songs

were the first new "Beatles" tracks in 25 years. Yet, for all the

responsibilities of that high-pressure assignment, Lynne says reanimating John

Lennon for a pair of songs was less stressful than the task of completing

Brainwashed. "Absolutely, because that earlier effort was shared amongst

three other Beatles. That was, like, easy I suppose, because I didn't know

John-although I'd met him once-and I'd been asked by the rest of the Beatles to

come help with it. "But Brainwashed was kind of a different scenario. Those

songs were new and fresh. And, you know, I'd worked with George for many years,

and been his pal and hung out with him for a long time. Working on

Brainwashed was a labour of love. But it was a very hard thing to do." In

March 2002, Lynne, with Dhani, got down to sorting through Harrison's demos at

his Bungalow Palace studio, in L.A., employing a Pro Tool HD setup he had

purchased for the occasion. Much to Lynne's pleasure, the recordings were close

to complete. In addition to guitar and ukuele, Harrison had laid down all of his

lead vocals, as well as harmonies and bass tracks that had been recorded with

legendary session ace Jim Keltner, and parts by keyboardist Jools Holland.

"The first thing we did was scour every track," says Lynne. "To

my great happiness, George left us with all these great slide guitar solos,

which I was totally thrilled with. You know how when you make demos you try out

different ideas on different tracks? Well, there would be, like, three or four

different takes of solos. Amongst them, he'd left us some beautiful stuff, and

sometimes we'd switch tracks halfway through another track, like you might

normally do when working on an album. And from it we were able to create what we

imagined to be the lead guitar track of his choice." Even so the songs were

far from ready to be released. "There was a lot of tidying up to

do," says Lynne. "Like, on some songs he'd play the bass and he'd sort

of trail off and lose interest in what he was doing. And so I would have to

finish some of the bass tracks, just to make them complete. In some cases, he'd

left the songs in a real state that we couldn't really follow unless we worked

like Sherlock Holmes. We had to go through each track and figure out what was

going on."

Fortunately, Harrison left Dhani and Lynne details on what he wanted for the

songs' arrangements and production. Often the tapes themselves contained clues

to Harrison's desires for the songs. "For instance, on 'Rising Son' he sung

his ideas for the string parts onto the tape," says Lynne. "Marc Mann,

who played keyboard on some of the record, wrote out the parts that George had

sung, and Dhani added a little line on top of it. And so that became the

part for the string players. "But his instructions were sometimes cryptic,

as well. Like at the beginning of 'Any Road,' you can hear him say, 'Give me

plenty of that guitar!'  Something like that was a clue to how he wanted things

to sound." Key to Lynne and Dhani's efforts was one directive from

Harrison: it was his desire that the final tracks sound close to the demo form

in which he had left them. "I knew what he meant by that," says Lynne.

"Basically, he didn't want it smeared in reverb or anything like that, he

didn't want us to make it slick-which he knows I would never do anyway.

And although George had asked me not to make them posh, I still don't think

they're posh. I think they're exactly what he wanted." Lynne had the

benefit of have recorded Harrison on several occasions. In addition to producing

Cloud Nine and two Beatles singles, he had played with Harrison in the Traveling

Wilburys, the late-Eighties supergroup that included Bob Dylan, Tom Petty and

the late Roy Orbison, and had produced both of the group's albums as well.

"So I think George trusted me to get him the sound that he would

like." Beyond his own experience with George, Lynne was guided by the

advice and insight of the younger Harrison. "Having Dhani there was

confirmation, or nonconfirmation, of whether I was getting it right or not.

Dhani was really the guy who knew intimately what George wanted, because they

were so close. So that made it much easier for me. I would just look at Dhani,

and if something about him didn't look right I'd say, 'What is it?' And he'd

tell me. So I'd get little clues like that. And then once we'd done a couple of

tracks and they sounded really good, George was kind of with us. Because he was

there, coming out of the speakers."

Something like that was a clue to how he wanted things

to sound." Key to Lynne and Dhani's efforts was one directive from

Harrison: it was his desire that the final tracks sound close to the demo form

in which he had left them. "I knew what he meant by that," says Lynne.

"Basically, he didn't want it smeared in reverb or anything like that, he

didn't want us to make it slick-which he knows I would never do anyway.

And although George had asked me not to make them posh, I still don't think

they're posh. I think they're exactly what he wanted." Lynne had the

benefit of have recorded Harrison on several occasions. In addition to producing

Cloud Nine and two Beatles singles, he had played with Harrison in the Traveling

Wilburys, the late-Eighties supergroup that included Bob Dylan, Tom Petty and

the late Roy Orbison, and had produced both of the group's albums as well.

"So I think George trusted me to get him the sound that he would

like." Beyond his own experience with George, Lynne was guided by the

advice and insight of the younger Harrison. "Having Dhani there was

confirmation, or nonconfirmation, of whether I was getting it right or not.

Dhani was really the guy who knew intimately what George wanted, because they

were so close. So that made it much easier for me. I would just look at Dhani,

and if something about him didn't look right I'd say, 'What is it?' And he'd

tell me. So I'd get little clues like that. And then once we'd done a couple of

tracks and they sounded really good, George was kind of with us. Because he was

there, coming out of the speakers."

The greatest part of George Harrison's music career was already behind him when

Dhani, his only child, was born in 1978. the product of Harrison's second

marriage, to Olivia Arias, the guitarist's one-time personal secretary, Dhani

grew up at a time when his father's activities were shifting away from music,

towards film production and Formula 1 racing. But at home, music continued to

play a central role in the family, and it was one means through which father and

son bonded. Not only did Dhani frequently hear his father's last songs as they

were developed over the years-he also performed on them at various stages in

their recorded life.

For Dhani, the experience of completing the tracks was exhilarating, if tempered

by the absence of his father. "When Jeff and I were working on the

song 'Rising Son,' it was one of the saddest and happiest things to work

on," says Dhani. "To hear the finished result, with the big strings on

it like my dad had intended-it was the best thing ever. And then to realize that

he never got to hear it, even though he probably just heard it in his head the

whole time-for me, it's still one of the saddest things ever. "And at the

same time, to go through my father's music with a fine-tooth comb made me see

things about him that even I hadn't realized: that he was even more impressive

that I thought he was. And that might sound like an arrogant thing to say,

but, you know...even though I knew what I had, you never quite know what you've

got until it's gone."

GW: Some of the songs on Brainwashed date back to 1988, when you were maybe all

of 10 years old. Do you remember the first time you heard them?

HARRISON: It's kind of hard for me to put a date on them because they've been

around for so long. For example, "Rising Son" was written on the Live

in Japan tour in '91. I remember my dad playing that around the house on the

ukuele. "Any Road" was written during the video shoot for "This

is Love" [from Cloud Nine]. He was in Hawaii, sitting in a banyan tree, and

waiting for the camera crew to film the video. Something like

"Brainwashed" is more recent. The songs were never really written

down; they were just songs he'd have in his head. He'd change the words

and change the arrangements, and he would just play the songs around the house.

GW: He obviously wasn't in any rush to complete them. Or was he waiting for

inspiration to strike?

HARRISON: We'd travel a lot, and these were his kind of travelling songs that

he'd just play and muse over and then do nothing with for a long time. A lot of

these songs were written very slowly because he was writing them for himself.

That's why they sound a lot less affected than anything else that you're hearing

at the moment. That's why they sound go good.

GW: When did he start actually committing them to tape?

HARRISON: They weren't actually recorded until the last few years. Some of them

were demoed before then: he'd have them on a cassette, or on tape, and he might

do a live mix, which he'd keep on a DAT. And then he might keep that for six

years! But he would work in the studio a lot by himself wherever we were.

We lived in Switzerland for a while, and we had a home studio there-Swiss Army

Studios. [laughs] A lot of the album was done there.

GW:

Did he ever intend to go beyond the demo stage with these songs and turn

them into full-fledge productions?

HARRISON: Actually, we'd planned to go to Jeff's studio in March 2001 to finish

up the tapes. But then Jeff had just finished touring for his [Electric Light

Orchestra] album Zoom, and he wasn't feeling well. And it was a bad time for my

dad as well, timing-wise, so we just decided to reschedule it for the following

March. And...what had happened was, in the meantime, my dad got ill and,

unfortunately, died. But we had the studio time booked, so I went ahead with

Jeff and finished the album.

GW: What was it like working with your dad in the studio?

HARRISON: Oh, we had some great times. Some days it would be me in there

pressing "play" and "stop," and some days we'd have

engineers, so we could play together. It was very relaxed, just me and him at

home in the studio. A lot of the time I would hear him play something that

sounded amazing, and I knew I would hear it turn up years later, or whenever the

album got done. And so when we were hearing all this stuff at Jeff's, you know,

I just had memories of being at home, really, or being wherever our home was,

'cause we'd record in Australia, on the road, in Japan, in Switzerland. But the

final recording material came from Switzerland. It was the most recent stuff

that my dad and I worked on. From Switzerland, we went to America, which is

where my dad died. After that I came home, and then I returned to America

with all the tapes.

GW: Your father had worked with Jeff Lynne on many recordings through the years.

The fact that he chose Jeff to produce Brainwashed says a lot about his trust in

him.

HARRISON: Jeff and my dad had a great way of working together. They were very

good friends, and Jeff was meticulous, and he'd have a lot of ideas and bounce

stuff off my dad. They just worked very well together. I think their studios

were set up very similarly, except Jeff had gone the next step, to integrating

Pro Tools. That was part of the reason why my dad wanted to work at Jeff's

studio. He said, "Oh, we can fix some of these little bits on Pro

Tools." Now, he was always against that idea before, but he sort of

softened up on the whole idea when he played guitar for Jeff on Zoom. And I

think he was really happy to be able to like Pro Tools instead of just fearing

it. [laughs]

GW: Did you and Jeff use Pro Tools to "fix" any of your father's

parts?

HARRISON: We didn't do any digital "cheating"-fixing of notes and

rhythms. It's so easy to do that, but we were very, very conscious not to

impose on the record's sound at all, 'cause it had a great, great sound. We

didn't want to leave our footprints on it at all. So if a track seemed to need

additional backing vocals, Jeff and I would add them because that's what we

would have done if my father had been there. We did the album pretty much the

same way it would have been done if he had been there. Only it was harder

because he wasn't there, and we didn't have his feedback. Which was impossible

some days.

GW: How helpful were the instructions he left behind?

HARRISON: He wrote lots of notes and left a very, very detailed blueprint for

everything. But it wasn't written as "these are the instructions"; was

more about what he had planned to do with the songs himself. But since I had

talked about the album with him, and I had been in the studio with him for years

and years, the majority of the instruction for me and Jeff came from my being

there watching what my dad did every day. We were so close, it was just

obvious certain things that should be there and shouldn't be there.

GW: Can you give me an example?

HARRISON: Well, like the bass guitar: my dad didn't really care much about the

bass. He'd stick a bass on a song, and after four verses he'd change the

riff. So sometimes we'd use his bass part all the way through. But a

lot of the time Jeff and I would redo it entirely. We'd play exactly the same

bit that my dad would play, only it would be metronome perfect.

GW: He obviously took more care with his ukulele parts. The instrument is all

over Brainwashed. When did your father become such a fan of the ukuele?

HARRISON: Wow! [laughs] That's a good question! He loves the uke. I think

he ended up getting into it in the late 80s, when he got interested in George

Formby. I mean, he's playing it all over the [Beatles'] Anthology video.

And the whole time I was growing up there've been ukes all over the house.

Even I've played the uke since I was really young. My dad showed me how.

GW: Well, of course!

HARRISON: [laughs] So we played together. And, you know, you can't not like the

uke. There was a point, I remember, when it was not cool when I was

younger, but it won me over. And he got a great collection of ukes, and

banjuleles, resonator ukuleles that haven't been made for god knows how many

years-just all kinds, every shape and size of uke. For him I think it was

just a silly way of being able to just play a tune. But when you get good at it,

it's really not very silly. I mean, I play the uke every day myself, and I know

a lot of people who do too.

GW: Did your dad ever mention to you that John Lennon's mother played the

ukulele?

HARRISON: I think he might have mentioned it to me once, actually. And I think

maybe that's why he had a fondness for it. I'm not saying that's a direct

influence. But I'm sure it could have been a subtle influence.

GW: He must have taught you guitar as well.

HARRISON: Yeah. He just showed me all the chords. He didn't show me any songs,

really. He showed me all the chords that I could possibly cram into my head, and

then I had learned all those, then he made me just practice changing between

them. I picked it up pretty easily, really. I used to play piano when I was

young and, I have to say, I struggled pretty hard to read music. I just play by

ear, and music teachers don't really like that, because they want you to read

the notes. And I remember having an altercation with my teacher when I decided

that I was never playing piano ever again, because my teacher was mean.

But then soon after that I got a real urge to play the guitar. And so my

dad, who'd never ever forced a guitar on me or so much as showed me a guitar

[laughs]-really!-we just started playing guitar together. I was about nine.

GW: Did he ever share any of his technique with you? His slide technique, for

example?

HARRISON: You know...no! Not his slide technique. I mean, I watched

the guy play slide a million times, and I can't even tell you how he got those

sounds!

GW: Was he particular about using, say, a glass slide versus a metal slide?

HARRISON: He used glass slides. And he had a favourite one that was cracked and

had a bit of tape on it. There was nothing special about it; it was just a glass

slide about the diameter of a mic stand. And that's what he used. Playing

slide was just something that was his gift. In my opinion, the slide

playing on this record is some of the best he's ever done. And he was a real

"take over" kind of guy.

GW: There seems to be potential for people to listen to some of these songs and

think, Ah, he's writing about dying. For example, "Looking for My

Life" he sings, "Oh Lord, won't you listen to me now/Oh Lord, I've got

to get back to you somehow." The song seems to present a man who's

lost touch with God, who's now trying to reconnect with God because of some dire

occurrence in his life.

HARRISON: Well, some songs were written prior to his illness and some during.

And his illness did have an impact on his songwriting. But you have to

realise that he never sat around moping, "Oh, I'm ill." Even

when he first found out that he was ill, years ago [in 1997], and the doctor

gave him-what?-6 months to live! He was just like, "Bollocks!"

He was never afraid. He was willing to try and get better, but he didn't care.

He wasn't attached to this world in the way most people would be. He was

on to bigger and better things. And he had a real total and utter

disinterest in worrying and being stressed. My dad had no fear of dying

whatsoever. I can't stress that enough, really.

GW: But your father almost always wrote of his experiences. You don't

think the experience of having cancer and almost being fatally stabbed by an

intruder affected his outlook and made him more aware of his mortality?

HARRISON: I guess you would expect me to say that those things made him

readdress his whole principal of life. But that is simply not the case.

Those were things he was thinking years before he ever got ill, before he was

attacked, before any of that stuff. For instance, he was writing songs

like "The Art of Dying" a long time ago, back in the 60s, and that was

before he even felt ill. So with that song, "Looking for My

Life"-I just think he found himself in moments of desperation before he

became ill, when he was under no sort of danger but just desperately wanting to

know, "Why am I here?" He was really looking for his life the whole

time.

So it didn't take an attack or cancer for him to reflect on his own mortality-he

did it all the time. You know, he'd say, "One of these days I'm gonna

be dead and you're gonna have to look after these trees!" And I'd be,

"Stop saying that, Dad!" And he'd be like, "But it's

true." Because he was a realist. And I'm very much the same way.

Everyone is gonna die, but no one thinks they're gonna die. No one. And

that's like the biggest blind spot that everyone in the world has, this

inability to believe that they're gonna die. And I think the sooner you

address that, the better, really. It's like practice, really.

GW: Did the experience of facing death bring him any new revelations about life

or make him re-evaluate his thinking?

HARRISON: My dad was constantly re-evaluating his thinking. He was always

saying, "The most important thing is, 'Who am I? What am I doing?

Where am I going? Why am I going anywhere?'" And to even ask

those questions-some people haven't even begun. So a lot of the music is

just posing questions, maybe to himself, yeah. Or maybe he's posing the

questions in his music because he's already found the answer for himself.

You know, I read a letter from him to his mother that he wrote when he was 24.

He was on tour [with the Beatles], or someplace, when he wrote it. And it

basically says, "I want to be self-realised. I want to find God. I'm

not interested in material things, this world, fame. I'm going for the

real goal. And I hope you don't worry about me, mum!" And he

wrote that when he was 24! And that was basically the philosophy that he had up

until the day he died. He was just going for it right from an early

age-the big goal.

GW: Of all the songs, "Brainwashed" presents the most revolutionary

message. It denounces everything we've come to accept in the Western

world, from our lifestyle to how we're governed. But it also seems to say,

"If we're such God-fearing people, then why don't we let ourselves be

brainwashed by spirituality?"

HARRISON: The song is very anti-establishment, just like punk music, or Rage

Against the Machine. And all that stuff is great. But a lot of the

time music that denounces what's happening in society doesn't offer an

alternative; it just says, "Well, this is wrong," but it doesn't say,

"Go and realise God," or, "Go and meditate for a bit." And

that's why I think "Brainwashed" is so strong-because of the contrast

that he presents in the song. It leaves you with something positive rather than

just denouncing the brainwashing and leaving you depressed.

GW: It gives you hope.

HARRISON: Yeah. Because, you know, my dad was very alarmed by the state of

affairs in the world. He was very disturbed by it. That's why he didn't go

out much, why stayed in his garden. Because he didn't like traffic jams

and mobile phones, and governments and war.

GW: Does listening to Brainwashed make you sad?

HARRISON: For me, it's not a sad album. I mean, the saddest it gets for me it

listening to "Marwa Blues." And that's a real beautiful song,

but it's also like a real lament. It's a man who wants to be somewhere

else, or searching for something else. And it's got no lyrics! So it

might not necessarily be that the sad songs are "Looking for My Life"

or "Stuck Inside a Cloud." With my dad, it's hard to tell,

unless you're really close to him. I don't know: anyone who looks at life

the same way would get it, but not many people really do.

GW: It's odd, but in several pictures of your father taken in the last few years

of his life, he looks much younger than the had 10 years earlier, even though he

was ill. And in that time, he wrote the songs on Brainwashed, which are

among the finest of his career. Someone recently said to me that trees

blossom most beautifully in their final season. And the analogy to your

father seemed rather appropriate.

HARRISON: Yeah...I think that's right. They

do.

Back

to Home Page

In

the final years of his life, George Harrison often predicted that he wouldn't

finish the tracks that make up Brainwashed, his new, posthumously released album

on Dark Horse Records. It wasn't his fight with cancer that the former Beatle

guitarist believed would prevent him from completing the recordings-it was his

own indifference. Harrison had little desire to see his work released in a pop

culture climate controlled by an increasingly cynical and money-grabbing music

industry. An inveterate nonconformist-the mark of a bona fide rock and

roller-Harrison had throughout the 80s become increasingly disenchanted with the

fickle and unsupportive nature of the record business. He spent much of his last

decade at his Friar Park, estate in England, or at his homes in Switzerland,

Australia and Hawaii, preferring the flowers in his gardens to the songs

germinating in his head.

In

the final years of his life, George Harrison often predicted that he wouldn't

finish the tracks that make up Brainwashed, his new, posthumously released album

on Dark Horse Records. It wasn't his fight with cancer that the former Beatle

guitarist believed would prevent him from completing the recordings-it was his

own indifference. Harrison had little desire to see his work released in a pop

culture climate controlled by an increasingly cynical and money-grabbing music

industry. An inveterate nonconformist-the mark of a bona fide rock and

roller-Harrison had throughout the 80s become increasingly disenchanted with the

fickle and unsupportive nature of the record business. He spent much of his last

decade at his Friar Park, estate in England, or at his homes in Switzerland,

Australia and Hawaii, preferring the flowers in his gardens to the songs

germinating in his head.  upon Harrison's sanctuary hang ominously, and

it's here that the lyrics become more confessional. "I never knew that life

was loaded," he sings on "Looking for My Life." "I never

knew that things exploded/I only found it out when I was down upon my

knees/Looking for my life." "Obviously, his illness had an input

into the songs," says Dhani. "And it influenced the way he wrote songs

and the way he saw life. But my dad never let anything get him down. He was a

tough guy. He just got up and carried on."

upon Harrison's sanctuary hang ominously, and

it's here that the lyrics become more confessional. "I never knew that life

was loaded," he sings on "Looking for My Life." "I never

knew that things exploded/I only found it out when I was down upon my

knees/Looking for my life." "Obviously, his illness had an input

into the songs," says Dhani. "And it influenced the way he wrote songs

and the way he saw life. But my dad never let anything get him down. He was a

tough guy. He just got up and carried on." Something like that was a clue to how he wanted things

to sound." Key to Lynne and Dhani's efforts was one directive from

Harrison: it was his desire that the final tracks sound close to the demo form

in which he had left them. "I knew what he meant by that," says Lynne.

"Basically, he didn't want it smeared in reverb or anything like that, he

didn't want us to make it slick-which he knows I would never do anyway.

And although George had asked me not to make them posh, I still don't think

they're posh. I think they're exactly what he wanted." Lynne had the

benefit of have recorded Harrison on several occasions. In addition to producing

Cloud Nine and two Beatles singles, he had played with Harrison in the Traveling

Wilburys, the late-Eighties supergroup that included Bob Dylan, Tom Petty and

the late Roy Orbison, and had produced both of the group's albums as well.

"So I think George trusted me to get him the sound that he would

like." Beyond his own experience with George, Lynne was guided by the

advice and insight of the younger Harrison. "Having Dhani there was

confirmation, or nonconfirmation, of whether I was getting it right or not.

Dhani was really the guy who knew intimately what George wanted, because they

were so close. So that made it much easier for me. I would just look at Dhani,

and if something about him didn't look right I'd say, 'What is it?' And he'd

tell me. So I'd get little clues like that. And then once we'd done a couple of

tracks and they sounded really good, George was kind of with us. Because he was

there, coming out of the speakers."

Something like that was a clue to how he wanted things

to sound." Key to Lynne and Dhani's efforts was one directive from

Harrison: it was his desire that the final tracks sound close to the demo form

in which he had left them. "I knew what he meant by that," says Lynne.

"Basically, he didn't want it smeared in reverb or anything like that, he

didn't want us to make it slick-which he knows I would never do anyway.

And although George had asked me not to make them posh, I still don't think

they're posh. I think they're exactly what he wanted." Lynne had the

benefit of have recorded Harrison on several occasions. In addition to producing

Cloud Nine and two Beatles singles, he had played with Harrison in the Traveling

Wilburys, the late-Eighties supergroup that included Bob Dylan, Tom Petty and

the late Roy Orbison, and had produced both of the group's albums as well.

"So I think George trusted me to get him the sound that he would

like." Beyond his own experience with George, Lynne was guided by the

advice and insight of the younger Harrison. "Having Dhani there was

confirmation, or nonconfirmation, of whether I was getting it right or not.

Dhani was really the guy who knew intimately what George wanted, because they

were so close. So that made it much easier for me. I would just look at Dhani,

and if something about him didn't look right I'd say, 'What is it?' And he'd

tell me. So I'd get little clues like that. And then once we'd done a couple of

tracks and they sounded really good, George was kind of with us. Because he was

there, coming out of the speakers."